Film Log #15 – 1.2025

The Brutalist

Screened 1.20.25

Concision is the known concealer of truth, and this is going to be anything but concise.

Also, with total awareness that this post is going to come across as some aging man’s inability to communicate and connect with a younger generation’s art (this is from a “young” filmmaker, though I am all of five years older than director Brady Corbet) – I can’t avoid that I’m still trained to consume media, then provide insights.

So here goes.

NON-SPOILER information:

Mid-20th Century American cars, clothes, jazz, architecture, etc. All things I’m a sucker for.

I saw one trailer. I didn’t do further research because the trailer did its job. My interest was more than piqued. Furthermore, I was starving to see a new release in a theater so that’s partially to blame for my eagerness.

The movie is long. Which is fine; I actually enjoy intermissions. Hell, I wish all films longer than 100 minutes provided intermissions.

Assuming you basically know what the film is about – here’s one aspect of the many shared traits of contemporary cinema. The majority of characters are awful. Awful.

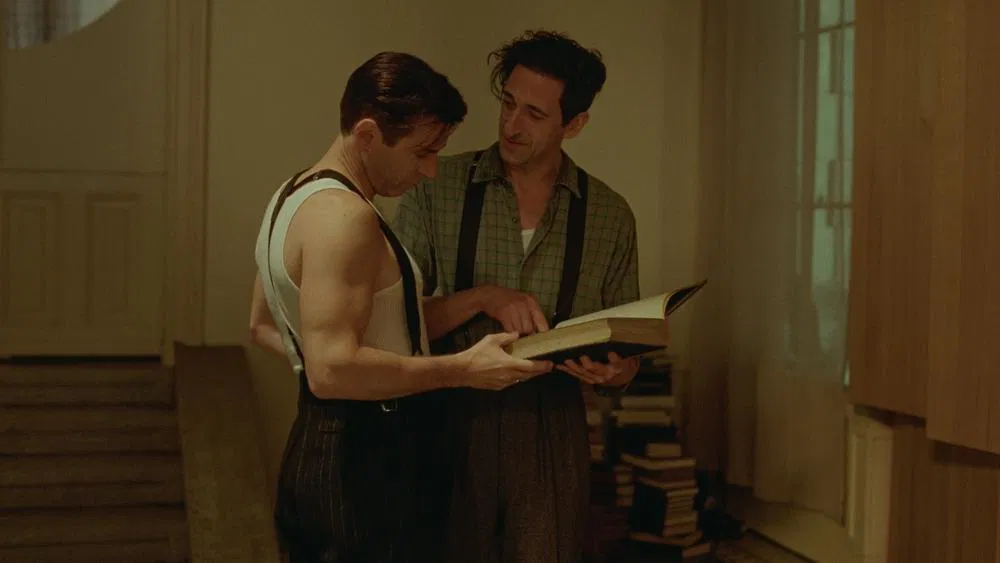

Adrien Brody does a fine job portraying Laszlo Toth, an Hungarian-Jewish architect that survives the Holocaust then immigrates to the U.S. He’s not perfect, his imperfections provide desperately-needed layers, and the post-war challenges he faces in America are, more or less, the film’s main point.

Alessandro Nivola plays Attila, Laszlo’s cousin in America who opens his home and provides professional opportunities to Laszlo. As often as Jon Hamm plays law enforcement characters, Alessandro Nivola plays an asshole who looks good in a suit and whose screentime is criminally limited. I like Nivola. His character should have been in the film longer, but due to the film’s first in a series of terrible turns, they experience a sudden split over an irrational mountain-out-of-a-molehill issue.

Succinctly put – the audience spends more than forty-five minutes getting to know Attila, and then the relationship is unnecessarily amputated, removed from the film entirely, over an issue that’s beyond flimsy.

Okay, now what?

While working for/with Attila, Laszlo meets members of the Van Buren family – a family consisting of wealthy industrialists. The Van Burens are terrible and basically stand in as a group of WASP antagonists. Great.

Before I get to spoilers, the only character that provides any shallow tension to the film is the patriarch of the Van Buren family, played by Guy Pearce. He’s complimentary, but also insulting. He provides, but there’s always strings attached. He’s supportive, but also terribly judgemental.

This, as well as Toth’s addictions and marital issues, pretty much comprises all the wobbly, incomplete tensions in the film.

The above, more or less, covers the first half.

I’ve discussed tension and character development in previous posts.

To reiterate, the construction of Laszlo’s character is fine. The “narrative world building” is fine.

With the exception of Guy Pearce’s Van Buren, every other character is terribly flat. One easily puts the tertiary characters into the “good/helpful” or “bad/threatening” bucket and, whatever set pieces have been laid, the paths these pieces fall into are inexplicable and irredeemable.

What’s more, it’s not like the film doesn’t have enough time to flesh important aspects out. They clearly weren’t concerned about keeping the film under the standard 90-120 minutes. Nope, it runs for 215.

Quick hits before moving onto the spoilers:

–This was one of the weirdest depictions of heroin use I’ve ever seen. The film attempts to sex up heroin in a head-scratching manner while also seeming blatantly inaccurate.

But what do I know? Maybe heroin empowers disabled people to walk and enhances sexual performance? I wouldn’t know firsthand, but I don’t believe it does.

–To elaborate on Pearce’s Van Buren benefactor-turned-villain role, the role has the makings to succeed, but ultimately fails. Though weak, the tension is there. But then every positive narrative trajectory gets violently thrown off a goddamn cliff.

–To quote what a feminist critic told me, “there is no redeeming female character. And all the female performances were… certainly less-than-good to put it charitably.”

I am sometimes concerned that because I repeatedly harp on how contemporary films are telling stories “the wrong way” that the reader may believe I think there’s a “right way.” There’s not a singular correct way to make a film, tell a story, present a narrative’s villain/antagonist relationship to a hero/protagonist (and some quality stories don’t even always need an antagonist – sometimes the piece is about interesting people in unique circumstances). That said, The Brutalist is an outstanding example as to how to waste a narrative.

Anyways, I’ll avoid bringing up antiheroes, but there are antagonists who are clearly the villain that the audience is supposed to root against, but we’re also simultaneously captivated by them.

Examples: Dr. Hannibal Lecter, Darth Vader, Christoph Waltz as Hans Landa, most Peter Lorre roles, anytime Phillip Seymour Hoffman plays a villain (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Punch Drunk Love), Louise Fletcher as Nurse Ratched, Henry Fonda as Frank in Once Upon a Time in the West, Ralph Fiennes in a few roles including Amon Goth in Schindler’s List and Harry Waters in In Bruges, John Huston as Noah Cross in Chinatown, Robert Mitchum in a few roles (though many of his villainous roles could be perceived as antiheroes), Dennis Hopper as Frank Booth in Blue Velvet, Orson Welles as Harry Lime in The Third Man, Sir Ben Kingsley as Don Logan in Sexy Beast, Bob Gunton as Warden Norton in Shawshank and on and on.

Something these villains all do remarkably well is introduce and amplify tension. In many cases, they are tension incarnate. And though we’re anticipating the villainy these characters are going to perform, they captivate us. In The Brutalist, the initial tension is circumstantial (Holocaust survivor attempting to start a new life in America) and then prematurely tossed aside (the fickle complication with Atilla, his beloved cousin).

Pearce’s Van Buren begins to underhandedly introduce tensions with slights, insults, and other irritations. It’s made clear that it’s only a matter of time before Van Buren commits a heinous act. But what ever could this act possibly be?

The sloppy, repellent Van Buren son, also behaves in an abhorrent way to Laszlo’s niece as well as Laszlo himself. The strongest scene in the film includes a verbal standoff between the Van Buren son and Laszlo. The film could desperately use a few more scenes like that unfortunately singular one.

ONTO THE SPOILERS (and the second half):

To speak on the “weak” tension that is built – the audience is never given clarity or resolution on most of the injected tension, which makes the narrative feel poorly contrived; fraudulent.

Laszlo’s niece, Zsofia, who is mute for most of the film, has one speaking scene where she’s determined to move with her Zionist husband to Israel in its early years. Kind of a strange choice to have a 2024-produced film, advocating for Zionism as a solution to any problem, but, sure.

Speaking of Zsofia, there’s a scene where the Van Buren son speaks horribly to her during a celebration of a large ground breaking ceremony, and if we’re to believe that a sexual assault occurred, then that must’ve happened in complete silence considering it was a public place, near a swimming hole, and the provided audio allows us to hear other nearby on-going conversations, so… I don’t believe I’m thick or imperceptive, and I do believe the Van Buren character is capable of committing sexual assaults, but the possible assault is ambiguous or barely implied because the director only wanted to inject tension without having to resolve it.

I believe the film purposefully cuts away from this scene to allow the audience to craft how benign (an attempted, but successfully defended advance/grope) or destructive the act was.

FINE. Do that. But now we’re left wondering, “so… when is Zsofia going to tell her aunt and uncle about the Van Buren son?” That is never addressed. Ad Lib storytelling is always a choice. I’d argue a bad one, but it is a choice. Conflicts don’t have to be explicitly spelled out, but why waste screentime on creating tensions only to arbitrarily discard the very tension you contrived?

Anyhow, speaking of arbitrarily manufacturing tension, Pearce, Brody, and crew members got to shoot in Carrara, Italy. Not sure why Van Buren and Laszlo have to see the Italian marble mines firsthand before Van Buren authorizes the purchase, there were already concerns with expenses and timelines for the construction projects, but anyhow, we’re now in beautiful Carrara, Italy. We get to see Van Buren, the racist fish out of water, away from his home, have to endure being in an impossibly beautiful location.

Van Buren and Laszlo attend a party. Laszlo receives some very positive social attention, and I guess because he’s an addict, he decides to shoot junk into his arm, and while engaged in his “dope fiend lean,” Van Buren rapes Laszlo.

OK. Yes, rape is about power and we have had to endure Van Buren petulantly throwing his power all around the camera dreadfully for most of the film. But this is not storytelling. This is how The Butterfly Effect told its story (which is a masterclass in asinine storytelling). Early in the film, we’re provided pussyfooted exhibitions of how evil and predatory American wealth is. Then this scene forces its way into the picture.

Do I believe that Rockefeller, Vanderbilt-types raped foreign architects in the 1950s? That’s quite a question. Sure? Maybe? No? Whatever answer I may provide doesn’t solve the problem with how befuddling this film’s narrative/character/directorial choices are.

To put it another way – what’s the worst thing that Van Buren could have done in this scene? Rape Laszlo, then douse him with kerosene, ignite him, then shoot him? That would’ve been about as subtle of a message.

So, this sudden rape scene takes place. What’s next for the audience and what’s next for the picture?

I’ll tell you what I did. I considered other films that have incorporated rape into their narratives (Shawshank, Blue Velvet, Irreversible, the list goes on) and contrast those examples with the gauche manner I just witnessed.

What’s next in the narrative? Nothing really.

For about 20 minutes of screentime, Laszlo predictably takes out his frustrations on those he loves.

Due to a difficult medical circumstance, Laszlo shoots heroin into his beloved wife and almost kills her, but not before enjoying the film’s only love scene between the two (what?!?!)!?!

The conclusion [thank God].

Erzsebet, Laszlo’s wife, who has been wheelchair bound throughout the picture, now, with the assistance of an aluminum walker, very slowly walks to the Van Buren compound and intrudes upon a dinner where she accuses Van Buren of raping Laszlo.

It would be silly to expect any form of 1950s legal/criminal reprisal to befall Van Buren, the American titan of industry, over an accusation of a rape that occurred on foreign soil. But what conclusion was I hoping for?

I’m not sure. Maybe the all consuming construction project Laszlo was working on is completed, unveiled, and there are some secret additions or some sort of architectural nod to the Van Burens being nothing but revolting rapists and capitalist pirates? Perhaps a scene where Van Buren and Laszlo actually discuss the crimes the Van Buren family has committed against the Toths giving the audience a type of Daniel Plainview/Eli Sunday conclusion? Anything to resolve whatever tension has been clumsily manufactured would’ve been better than the conclusion we were given.

What we got immediately following the dinner intrusion, was the Van Buren son shoving/kicking Erzsebet to the floor, then dragging her out of the dining room.

The camera cuts. Vanished is Pearce’s Van Buren (he’s an old man – can’t imagine him having incredible speed and agility) as well as Erzsebet (she is disabled – not going anywhere in a hurry). There is, strangely, a near instantaneous search party to find the elder Van Buren. I wouldn’t describe the final search party shots around Laszlo’s building as a particularly grand reveal of this enormous construction project the bulk of the film has built up, as those shots are severely limited.

In my eagerness to leave the theater, I may have missed this, but according to Wikipedia, a body is found, but not identified, by the search party. At that point, I didn’t care. It could’ve been Van Buren. It could’ve been Jimmy Hoffa. One would’ve made about as much sense as the other.

After all this rubbish, there’s an inexplicable flash-forward to the 1980s where, now elderly, Laszlo Toth is honored at an architectural biennale (and Zsofia’s character, now much older and portrayed by a different actress, does most of the speaking – so, Zsofia’s character technically has two speaking scenes). No mention of Van Buren, there is a vague reference to Erzsebet’s death, and a forgettable speech about Laszlo’s architectural achievements.

Though I was hopeful, this was frustrating.

I have regrettably put off screening Once Upon a Time in America, but there is no way I’ll watch another 200+ minute film before I watch that one. I sincerely wish I had given that a go instead of succumbing to the desire of watching a contemporary film in a theater. Life is too short for terrible cinema, and, goddamn, I wished I had used these three-plus hours to watch Once Upon a Time in America or drive to Health Camp in Waco to consume a shake and a burger or dozens of other things before watching this film.

I intended to tie in the failures of this film (which was nominated for 10 – TEN! – Academy Awards) and how they are similar to failures of other acclaimed contemporary films I’ve seen, but this post is already too long. That may come sooner than later though.

During my formative years, I saw media/entertainment as bifurcated. It was either dumb or smart. Thoughtful or thoughtless. Perspective broadening or narrowing. I made a silly website discussing that development. That viewpoint was sometimes foolishly applied to other aspects of my life.

It’s disheartening to see entertainment become dumb or dumber and watch the industry fall all over themselves handing out awards for senseless bunk. Come March 2nd, this picture may win upwards of five or more prestigious awards and it’ll be another example of how this rock revolving around the sun makes less and less sense to me.

Note – The Brutalist does have nominations that have nothing to do with acting or narrative structure such as editing, cinematography, production design, and original score. And I suppose those aspects of the film are good, but I obviously don’t watch enough contemporary cinema to know whether or not they’re better than its peers.